In fight over jet, Miami developer files defamation suit over debunked bribery claim

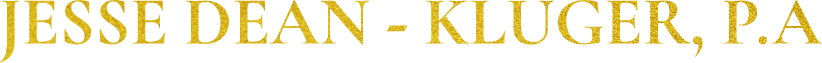

A legal clash between Ugo Colombo and Craig Robins, two of Miami’s flashiest developers, involves a luxury private jet and nearly a decade of bitter accusations.

The latest came in December, when Robins’ companies — on the hook for at least $3 million after losing at trial — alleged in a lawsuit that Colombo or his people won by secretly paying off a juror and promising him a luxury condo.

One problem: Miami-Dade prosecutors debunked the bribery claim years ago.

Colombo’s side is fighting back, filing a defamation lawsuit on Wednesday against Robins and one of his lawyers, Dennis Richard. They’ve also filed a motion to throw out Robins’ December lawsuit as a “sham pleading,” and included a sworn affidavit from the juror denying the accusations.

“We feel very strongly in this case there has been no wrongdoing and this lawsuit should not have been brought,” one of Colombo’s lawyers, Thomas Scott, told the Miami Herald.

Andrew Berman, a lawyer representing Robins’ companies, declined to comment on Wednesday.

Colombo is the developer behind Downtown Miami’s Epic Hotel and played a “pioneering role in the development of Miami’s downtown skyline,” says his lawsuit. His CMC Group is also behind the 541-unit Brickell Flatiron tower, which is slated for completion later this year.

Robins is the developer behind Miami’s Design District, and is married to Jackie Soffer, the CEO of Turnberry Associates and part of the prominent family that owns the Fontainebleau Miami Beach hotel. His legal team was not immediately available for comment.

Their seeds for the legal strife began over a decade ago when Colombo bought a $22 million Bombardier Challenger jet. One of Robins’ companies, Dacra Development, owned half the plane and the two sides jet-setted around the world with no problems.

Until 2008. Then Colombo claimed that Robins took a round-the-world trip and refused to pay bills owed to Turnberry Management, which the two developers had hired to manage the aircraft. Turnberry sued Robins, who countersued and accused Colombo of reneging on a verbal agreement to buy ownership of the entire jet.

In March 2014, a Miami-Dade civil jury sided with Colombo, awarding him $2 million. A judge reduced the amount to $1.5 million.

Three years later, a court ordered Robins’ company to pay another $1.5 million in attorneys’ fees and other costs. Another of his companies, CL36 Leasing, is also on the hook for $28,000.

The legal fighting over the verdict has dragged on for years. A Miami-Dade judge last spring allowed Colombo to pursue punitive damages against Robins himself, a decision recently upheld by higher courts.

Then in December, Robins’ legal team filed a bombshell lawsuit seeking to set aside the 5-year-old verdict. Their allegation: Back during the 2014 trial, a juror named Roderick Brooks was approached by a mystery bag man and agreed to side with Colombo in exchange for a cash bribe and a highrise condo that might be worth up to $1 million.

According to the lawsuit, Brooks soon after the trial bought a big-rig truck for $26,829.77, using all cash.

The lawsuit offered only as evidence that Brooks had “since admitted the illicit contact” to a “third party” who later swore to the confession in an affidavit. That affidavit, however, was not included in the lawsuit and will be filed under seal, according to Robins’ lawyers.

The allegation was big news in South Florida’s real estate and legal circles, with stories published in the Real Deal, Law360 and the Daily Business Review. Richard said that bribery accusations are “grave.”

“Efforts to obfuscate those facts will not make them go away,” Richard told the DBR. “The consequences of jury tampering are severe.”

The lawsuit, however, makes no mention of the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s investigation, launched in October 2016 after Richard complained to the public corruption unit.

Investigators interviewed several of the jurors, including Brooks, who explained he bought the truck using an inheritance and money drawn from his retirement account. “The financial documentation provided was consistent with Brooks’ explanation,” Assistant State Attorney Tim VanderGiesen, the head of the public corruption unit, wrote in a final memo closing out the case.

The memo also pointed out that Brooks was actually the “holdout” juror in favor of Robins’ company. He eventually was swayed by other jurors to vote in favor of Colombo.

Colombo’s lawyers say Robins’ legal team knew that prosecutors had closed the case. They call the lawsuit a “Hail Mary” to avoid punitive damages, and a closer inspection of Robins’ finances.

“This knowledge, however, did not stop them from making false and malicious accusations in this case,” Scott wrote in the motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

Another of Colombo’s lawyers, Jesse Dean-Kluger, ripped Richard, the fellow lawyer.

“Dennis Richard’s conduct is insidious. It puts our judicial process in jeopardy,” he told the Miami Herald. “The allegation that he allowed to be made, when he knew they were false, attempted to make a mockery of our system and hold it up to ridicule. Lawyers like that should be severely disciplined.”

This article was originally published on Miami Herald.